Anna viewing Taxonomy exhibition prints in the studio of Bergkvara kulturmagasin 2022

Bergkvara residencies are intended for research and reflection. Our goal during this visit was to explore the future through the framework of the Breadboy Of Herculaneum. To begin we decided to identify a space-specific environmental problem where we could experiment with developing examinations based on artistic and scientific research methods as well as experiments with pyrolisation techniques. Through conversations with local authorities, private individuals, and general research we decided to work with the fertilisation runoff in to the Baltic sea and that the entry point to this problem would be the overgrowth of reeds. If these are left to die back naturally in the winter the problem will be exacerbated so each fall they are cut down to avoid further nutrients being added to the already overstressed system. While cutting them in the fall has the benefit of the reeds binding carbon and absorbing nutrients while they are growing one is also left with a rest product that one needs to find a use for or it will during the decay release the carbon it has stored during its growth.

To learn more about the circular systems and how nutrients and biochar can interplay in different ways we visited Ödevata experimental farm, hotel, and energy producer. Our interest in their work stemmed from their activity with biochar which turned out to be more sophisticated than we had expected. The images above picture their greenhouse and an aquaponic system with a fishpool (Pilatia) at the top of a row of containers filled with biochar where banana plants with fully developed bananas, passion fruits, and several other plants grow. It works by that water from the fish tank overflowins to the containers with biochar. As the water moves through the char it soaks up the waste from the fish creating fertile ground for growing. The water is subsequently, pumped back into the fishpool again creating a circular system. The greenhouse is heated by a pyrolisation kiln which is a CO2-negative carbon-capturing technique that stabilizes the carbon in the feedstock by producing the biochar. Biochar has many uses but is most usually used as a soil conditioner. The system is an experiment in circular, nontoxic ways of developing a year-round-growing system for the future that can be implemented in Urban areas.

The Ödevata Heat Pump 2022 This produces biochar and heat which is carried through a water system to the greenhouse. It was originally designed as an incinerator but to avoid releasing CO2 Magnus and Malin redesigned the kiln to pyrolise so that they could sequester the carbon.

Lisesgården 2022

At Ödevata we were also told about another project called Lisesgården which is being renovated by Lise and Maggan Johanson to serve the community as a heritage activity house where one can learn and familiarise oneself with new and old sustainable techniques. Having lived on the land all their lives they are made aware on a daily basis of the many dangerous changes we are facing and the risks unreflected decisions may have to the future of the global biosphere. The old farmhouse is surrounded by grazing grounds in a mixed open canopy forest and a burn where Lise’s sheep reside. Lise and Maggan hope this house will provide an antidote and shelter for slow and considered learning of more sustainable and useful strategies. They also own a biochar kiln of the Kon-tiki type and during our visit to them we agreed that they would give a performance to see how charing reed would work during the opening of our show at Bergkvara Konsthall

Lace pillow and bobins at Lisesgården. 2022

Before we arrived in Bergkvara we had begun a conversation with Torsås municipality's environmental inspector Pernilla Landin about the possibility to make biochar from reeds and try to use this to filter the runoff water. The municipality had previously tried to use the reed cutoff for other purposes such as in incinerates with a view to use it at the district heating plant. This had not worked because the silica in the reed rapidly clogged up the chimney. While our plan to use an open cap kiln would eliminate this problem we double-checked with Skånefrö district heating plant if a closed pyrolisation technique would pose the same problem. We found it wouldn't because burning feedstock in the environment of a biochar kiln does not bind gasified compounds to oxygen simply because there is no oxygen to bind to. The municipality is interested in finding another use for this waste product and Pernilla gave us access to the last years of cutdown reed.

Anna by Reeds Bergkvara 2022

Biochar which essentially is the same as carbon is a very porous material. If it is being used as a soil conditioner one usually saturates it with some kind of organic nutrition. If it is used as a filter it can capture excess nutrition by storing water until the next drought and then feed water and nutrients back to plants and function as a flood defense simultaneously. To try out how easy it is to use biochar for filtering we had an idea to lower a sac of biochar into a drain well. With the help of Pernilla who came with us to take water tests and the farmer Bertil Aspenäs who gave us access to one of his manholes, we set about trying.

Areal map of covered drainage pipes in Bergkvara 2022

The experiment failed for various reasons. Firstly it turned out the manhole contained mechanisms where the sack would have risked getting stuck and damaging the vaults had we used it. Bertil has an unusual and very refined drainage system that enables him to pump the excess water from his fields into a storage dam during the rainy season where instead of flowing out into the adjoining waterbodies, is held to be pumped back to the field little by little where it is used by the plants in a closed circuit system.

We discover the vaults mechanisms. Bergkvara 2022

When the test results were returned some weeks later it turned out that the char had quickly captured the nitrogen but that it to our surprise had released a lot of phosphorous.

Excerpt test one and test two. 2022 Bergkvara

The whole experience led us to learn more about filtering techniques and that we would have to find a drain system that doesn’t have the water storage systems Bertils fields has. We began with inspecting another filter arrangement that Ödevata has in order to try to figure out another method for the drainage system which is pictured below.

Hängning Bergkvara 2022

At our exhibition, we showed some of the initial work we made 2019 and some that were made in 2022. For the performance, we had borrowed a kon-tiki kiln from Ödevata, and Lise and Maggan were bio-charing reeds and some wood we had collected in case the reeds would burn too fast. It turned out to work beyond expectations. We had been afraid that the reeds would be incinerated instead of charing but they chared in small tube forms looking exactly like they did before being charred but black and more brittle. Further reading on reed as biochar feedstock can be found here .

Carbon is the basis of everything and when it decays or is burnt to ashes the carbon combines with oxygen and becomes CO2. When carbon is captured, held, and released through natural systems such as in forests and plants that capture CO2 and transform it into oxygen through photosynthesis at optimal levels it creates among other things a balanced climate. The problem is that in our current carbon fossil fuel-driven world the natural system can no longer keep up with the amount of CO2 that is released which results in global warming and has devastating effects on everything in the biosphere. To reverse this we need to stop releasing carbon into the atmosphere by stopping burning fossil fuels, saving energy and creating carbon sinks. Pernilla and Maggan’s performance gave an opportunity to articulate the carbon cycle visually while also physically in realtime showing a simple carbon negative capturing technique

The images above are from Skånefrö a biochar-driven district heating plant. It uses waste materials from farming as feedstock and heats the village of Hammenhög. It seems like a useful development to look at for places like Scotland where they do not yet have a built-up district heating system. We are also asking ourselves the question if it’s possible to transform the Swedish distric heating ovens to a pyrolysis technique. This requires more research.

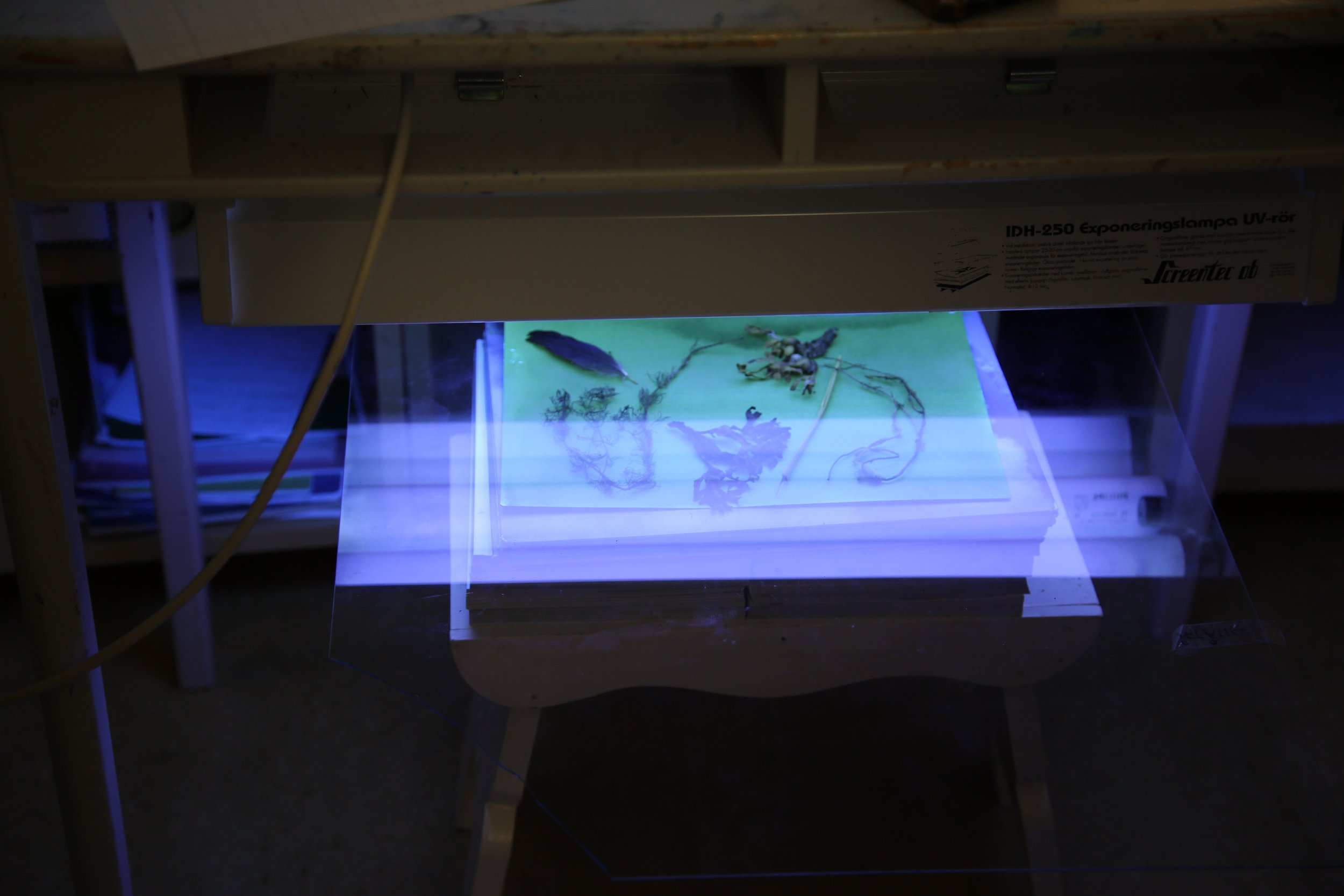

Another trajectory we followed was to do cyanotype workshops with 12-year-olds in the municipality’s 4 schools as a part of Skapande Skola. We used the botanist and photographer Anna Atkins images introduce the material, cyanotypes, and the subject, the loss of algae species due to the overgrowth of others in the Baltic sea. The visuality of each step in the Cyanotype process is useful to describe what happens in a photographic process to children who may never have seen an analog camera and Anna Atkins many multi-species algae cyanotypes provide a very useful counterpart to the very few printable species we managed to source off the local coastlines.

As it happened the students were very into making the work but we were not sure we were able to establish a sense of the loss that is occurring around them. They were theoretically aware of the disappearance of fish, the loss of oxygen causing mucky seafloor in swimming bays where there only a few years ago there was clean sand. The difference between the understanding we had hoped to generate and what actually happened suggests that it is very difficult to create a real sense of urgency about a loss if one never has had the experience of the thing that is lost. The classes however were only 3 hours and we do believe the work could go deeper if it was possible to do it during a longer period of time, perhaps even going out to the sea to collect things with the students rather than bringing it all to the classrooms.

Towards the end of our stay curator, Deirdre MacKenna who initially commissioned the work in Pietro’s house came on to have a seminar/talk with Maja Heuer a regional developer working for Kalmar Länsmuseum. The topic was cultural production as a societal building block and its importance to generate social cohesion and political agency in an increasingly atomized reality while facing a very possible complete destruction of the world as we know it. The conversation was framed through our work in Italy and in Bergkvara as well as through their different projects.

Deirdre to the left, Maja to the right. Bergkvara 2022

This talk seeded a thought that we hope to be able to gather everyone we have worked with during the Breadboy of Herculaneum to do a 3-day workshop which will culminate in a plan for transforming ancient fire traditions into sequestering rituals across the network. The celebration itself would take place on Beltane/Valborg on the 30th of April in our home locales (including Bergkvara) during a joint streamed event together with Ödevata where the new conceptualization of these ancient cleansing fire ritual traditions started last year.

Kåre Holgerson Chair of Bergkvara Kulturmagasin Bergkvara 2022

We have concluded that our stay at Bergkvara resulted in setting up several productive relationships with individuals and groups who we intend to continue working with. Some like biochar production is ready to be taken to the next step both in visualizing processes and performatively and others like the filtering process, the workshops, and our knowledge of the development of big kilns demand more research. We also hope our stay will facilitate a network between Casa Pleadi, Cultural Documents and Bergkvara Kulturmagasin.